Can You Hack Your Car? Part 1 of N

Synopsis

Last year, a friend of mine was visiting from overseas. They had recently purchased a Tesla and happened to show me a feature of the car I was not expecting. They pulled out their iPhone, opened up the Tesla app, and proceeded to control the interior temperature of the car, even though they were in a different country. In fact, there was a whole suite of things they could control from their iPhone, such as unlocking the car, flashing the lights, or honking the horn. This experience really stuck with me, and got me thinking, could I hack my car and create an app that would let me control it?

Initial Thoughts

Unlike the Tesla, my car is not an IoT device. In-fact, my car is old and doesn’t contain a myriad of options that come standard in today’s cars, such as a built-in GPS, a radio with Apple Car Play/Android Auto, or any other “smart” devices. This left me wondering how I could interface with my car from a computer.

How to Access a Car’s Data

Have you ever taken your car to a shop when the check engine light was on? OBD is how the mechanic is able to tell you what that check engine light means and what to do about it. OBD stands for on-board diagnostics, and mechanics (or even you) can plug a computer into this port to read and diagnose error codes coming from a car.

What’s interesting about the data coming out of the OBD port is that it contains much more than error codes. It can tell you the car’s RPMs, the engine temperature, the speed of the car, and even more.

I have read OBD data using smartphone apps such as Car Scanner. While this is useful, when I started thinking about all the different messages this app must receive and parse, I realized that I have never seen the raw data output from the OBD port. I have always relied on apps to ingest the data and display it for me. Because of this, I don’t know how this data is structured or what communication between the car and the OBD port looks like.

A Car, A Closed Network

If data can be read via the OBD port, this must mean there is some sort of network of communication going on inside of a car. For example, if we can read the RPMs from the OBD port, I imagine there must be some sort of RPM output that is constantly sending signals within a car’s network.

Because I am a software engineer, I imagined this as a API call that is constantly pinging the car’s “server” for more information about RPMs. If we theoretically model this in Python, it would be something along the lines of this.

from car import Car

vehicle = Car()

vehicle.connect()

while vehicle.is_running:

rpm = vehicle.get_rpm()

print(rpm)

Does this network of communications I am hypothesizing about exist, and if so, how do we access it? It turns out, most cars contain a closed network for communication known as CAN bus or controller area network vehicle bus. A vehicle bus interconnects the various electrical components inside of a vehicle and utilizes a protocol (such as CAN) to dictate how these various electrical components interact with each other.

Essentially, every electrical component (or node, SG below) in a car is connected via two wires and communicates by a protocol known as CAN.

The 120 ohm resistor on each end represents an “end” in the network. For example, one end is the car’s main computer and the other end could be an OBD device plugged into the OBD port of the car. Electrical signals are sent via the wires. These signals contain packets of data. When the network is idle, the voltage is generally 2.5 volts. CAN high runs at about 3 volts and CAN low runs at about 1.5 volts. These electrical pulses can be read as 0s and 1s and parsed for understanding of what is going on inside of the network. Each electrical pulse is essentially a message. This is known as a CAN frame or packet. A CAN frame roughly looks like the below table.

| ID | RTR | IDE | rO | DLC | DATA | CRC | CRC delimiter |

| Packet Identifier | Remote Transmit Request | ID Extension | Reserved Bit | Data Length Code | This is where the data lives | Cyclic Redundancy Check | |

| 11 bits (standard CAN frame) or 29 bits (extended CAN frame) | Tells you that one node is asking for information from another | Indicates an extended frame | Number of data bytes in the frame | 0..8 data bytes | Ensures that the received frame is intact |

Let’s look at an example of a CAN frame for context. Say that you change the radio station using a button on your steering wheel. When you push that button, a controller inside the steering wheel recognizes your request and sends a message to the CAN bus saying “Hey everyone, here is my ID and the current state of my buttons!” That message would look like this.

| ID | RTR | IDE | DLC | DATA |

| 0x0584 | 0x00 | 0x00 | 0x06 | 0x41 0x00 0x60 0x10 0x20 0x40 |

In this example, no extended frames are being used and the steering wheel is not requesting anything. That is why IDE and RTR are 0x00. This message is broadcast across the whole network of the car. Only one node knows how to handle this message, and that is the radio. The radio receives this message and then changes the station.

Since messages are broadcast across the whole car, and the whole car is a closed network, once you have access to the network, you should be able to intercept all messages in the network. Therefore, if we can add one more node to the network whose job it is to intercept all messages, we could begin to compile a log of all messages.

Once we have this log, and have correctly matched each message to it’s corresponding actions, we should be able to reverse engineer commands for each possible action. From here, we can reconfigure our node to send requests to the network.

For example, once we know what the CAN frame looks like for “roll down driver side window,” we should be able to create a program that can inject this message into a car’s CAN bus.

In other words, we have the beginnings of the back-end of an app that should be able to let us control a car 😈.

So how do we introduce this new node into the network? We have to go back to the OBD port.

New Node

We can build our own node using a special microchip and a microcontroller unit. We can then introduce that node to the car’s network via the OBD port with an OBD male plug connected the node.

Below, you can see the (rudimentary) node I have created.

I was fortunate that I already had an Arduino Uno to use as my microcontroller unit. The piece of hardware that I needed to order, and is necessary to make all of this work, was the smaller component covered in tape in the picture above. This is the MCP2515 CAN driver. It contains a microchip that can translate the CAN voltage into messages. This is key, because without this we wouldn’t be able to understand the data we receive from the car. I ordered the MCP2515 CAN driver from electromaker because it came bundled with the OBD male plug needed to interface with a car.

Once I received my hardware, I looked up the directions from the manufacturer on how they recommend assembling the components.

With new node assembled, we can now create the following diagram which represents the flow of data in and out of a car.

Car OBD ----> MCP2515 ----> Arduino ----> Personal

Port <---- CAN Driver <---- Uno <---- Computer

With our node plugged into the OBD port, we now have access to the car’s internal network. Essentially, data flows out of the car’s OBD port to the MCP2515. The MCP2515 translates this communication and sends it to the Arduino. The Arduino then connects to a personal computer via USB. From here, we can log all of the communications coming from the car for further analysis.

Now the only thing that is missing is some software on our personal computer that can read and log this information for us.

Software to Consume the Stream of Data

Again, following the manufacturer’s directions, I began to tinker with their C++ library for communicating with the MCP2515 driver plugged into the Arduino.

According to the directions, I need do these two tasks before I can read data from the OBD port:

- Set the baud rate of the board to 38400. (The baud rate determines the speed of communication over a data channel.)

- Set the mask and filter.

After doing these two tasks, I should be able to run another program, such as getRpm, to start reading the RPMs of the car.

However, I received this error when trying to do the first two tasks ☹️.

set can rate fail

set mask fail

set filt fail

I could see in the C++ library where these errors are being raised. I am led to believe that my personal computer is not communicating with the Arduino properly, which is not allowing me to configure the MCP2515. I attempted to run getRpm without the proper configurations just to see if it would work, and as I expected I received no data from the car even when the RPMs were high.

In-case this was a problem with the manufacturer’s C++ library, I found another library with similar functionalities that I decided to test out. However, I was also not able to read any data streams from the car using this library.

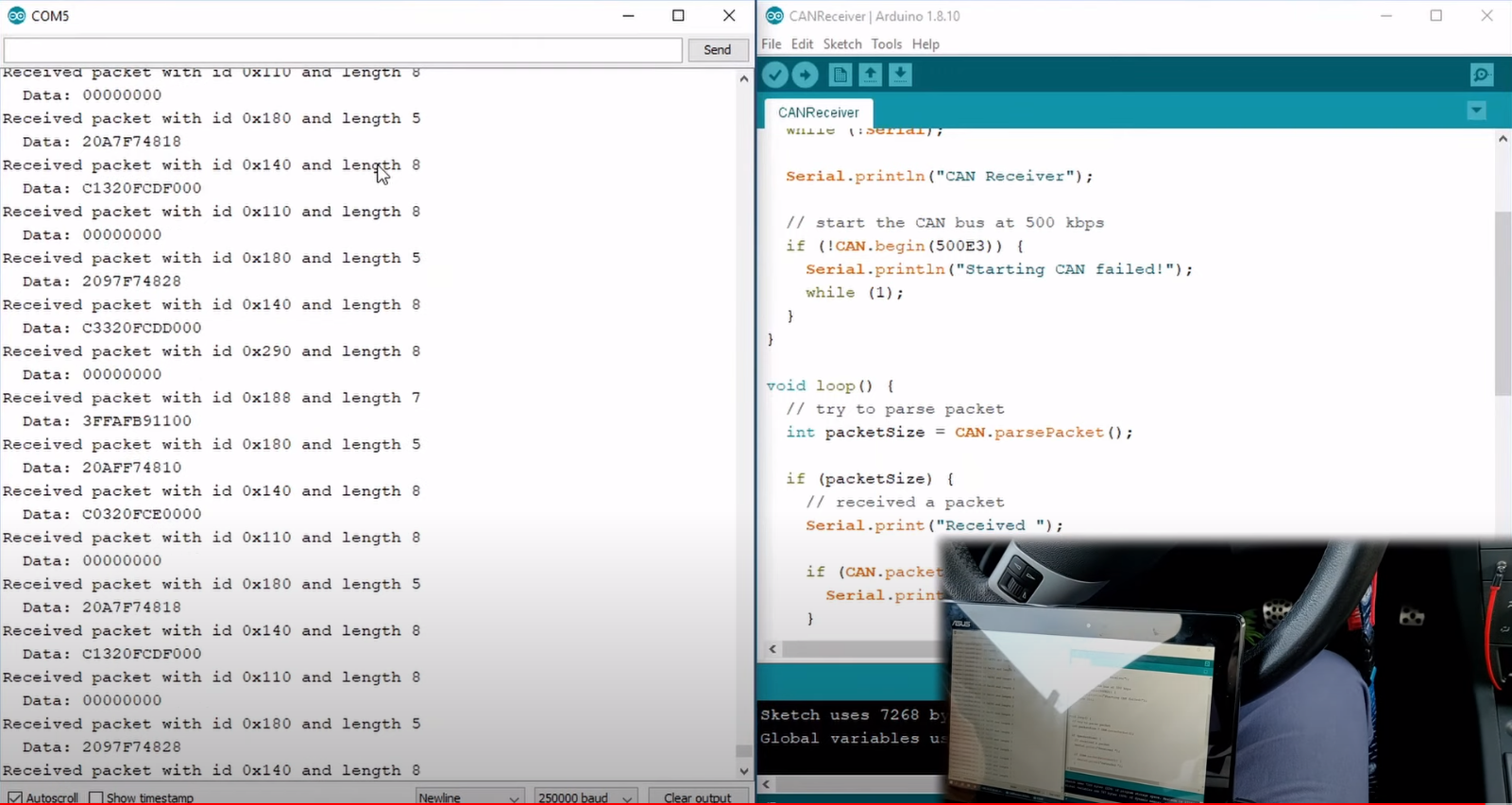

If all had gone as planned, I would have seen something like the below on my personal computer. On the left hand side, you can see a stream of CAN frames being received by the personal computer.

Next Steps

Since I had issues with two different software libraries, I believe that I may have wired something incorrectly on my node. I will need to revisit the manufacturer’s directions to double check that I have done everything correctly. If this fails, I will try to build the test environment with another Arduino and MCP2515 as described here.

Once we are able to read data from the car, we can then begin to log this information and translate it into commands. I believe that will be the next part of this series. The part after that will be taking these translations and sending them back to the car as command requests, which should effectively let us control certain functions of the car.

Recap

In this post, we discussed how to introduce a new node into a car’s internal communication network, known as a CAN bus, via a car’s OBD port. We created this node using an MCP2515 microchip with an Arduino Uno as a microcontroller unit. With this node, we attempted to read messages coming from the car’s communication network. We were unable to successfully read messages, thus, we need to revisit what we did to ensure the integrity of all of the different components involved in this (i.e., the hardware and the software).

Sources/Credits

This project involved quite a bit of electrical engineering. I am not an electrical engineer by trade. Everything I have learned comes from some amazing resources available on the internet and the help of some of my more knowledgeable friends and family. I have done my best to link to resources directly in the blog post above. I will include a few other sources below that helped me work on this project.

- How to hack your car | Part 1 - The basics of the CAN bus by Adam Varga

- Hacking Cars with Python by Evan Evenchick

- M-Systems Inc.

I worked on this project while attending the Recurse Center.